A Second Exodus

1956, Alexandria, Egypt

The wave was bigger than he had anticipated, knocking him off his feet and pushing him down under for a few seconds before carrying him quickly to the shore and spitting him out onto the sand.

At nine years old, Sami wasn’t the tallest kid in his class at the Lycée Francais, but he was strong and stocky. His naturally olive-toned skin was particularly tan after many afternoons at the beach that summer. He could have passed for an Egyptian, but even though the bustling cosmopolitan city of Alexandria, Egypt had been home to his family for generations, they were never considered Egyptian.

Sami emerged from the cool Mediterranean Sea, wiping the foam and sand from his brow as he pulled himself up. He loved everything about the beach: the sand, the water, the people, the colors. He could spend all day there, watching people, surfing the waves, munching on his favorite Caca Chinois candy, running and playing on the sand and in the water, his family’s private cabine serving as a home-base filled with his extended family – cousins, tantes and oncles.

“Sami, viens ici!” his mother called. He looked up to see her walking quickly toward him with a multi-colored towel held out, her shapely bare legs, tan and olive-toned just like Sami’s, emerging from beneath her blue bathing suit, and her rich brown hair pulled up into a colorful scarf. People said Jeanette was beautiful, elegant. But to Sami, she was just his mother.

My father, Roland Sam Malka was an only child, and more than a bit spoiled – un enfant gaté – by anyone’s account. He would hide his toys so he didn’t have to share. One time he went so far as to dig a hole in the ground and bury a toy he didn’t want his cousin Yves to play with. He got a taste of his own medicine when he later went to dig it up and couldn’t find the exact location where he had buried it. But he was charming and sweet, a golden boy with a good heart, so his brattiness didn’t keep his cousins from loving him.

No one ever called him Roland. Maybe it was too hard to pronounce in Arabic. Or maybe Sami just suited his playful personality better. Jeanette – my Nana – tended to coddle him a bit, not in a modern indulgent way, but in an old-world protective way. The only daughter of a wealthy Italian businessman, her family was part of the fabric of Alexandria.

Victor Malka – my Papi – had courted her and they had married, and once he had his son, he had felt no need to further procreate. Jeannette would have liked more children, but she didn’t argue with her husband. That just wasn’t done.

The Malka family lived an upscale life in a gorgeous apartment. Papi was a bank executive at Banque Belge and spoke six languages fluently. He also worked at the racetrack on weekends, helping with the spreads, the charts, the numbers. The only boy in a family with seven children, born right in the middle of his six sisters, he served as the patriarch of the family, making sure everyone was taken care of and that they all knew he had it all under control. He was also a charming ladies’ man, the life of any party, and there were many in the vibrant metropolitan city of Alexandria in the 1940s and 50s. It was an international hub of activity, life and culture. The Europeans who lived there enjoyed a peaceful co-existence with the Arabs. They spent their leisure time at the cinema, cafes, French patisseries. At the Alexandria Sporting Club, they played squash, tennis, cricket and golf, and enjoyed horseback riding and gambling. They spent weekends at the beach year-round, relishing in the mild climate.

Jews and non-Jews alike, the Europeans were welcome guests in Egypt. They ran the banks, the shops, the cinema, the racetrack. But despite the fact that Egypt was their home, their passports were French, Italian, British, etc. Some of them were technically apatride – stateless. They were neither Egyptian nor European, nor Israeli. They were children of the world.

At home and school, Sami’s family spoke mostly French, but they were part of a multireligious, multicultural and multiethnic environment. Abdul – the family’s servant who felt more like a big brother or an uncle – had taught Sami some Arabic.

The Malkas were among some 80,000 Jews who lived in Cairo and Alexandria, but they were not particularly religious. They followed the traditions of their faith quietly alongside their Muslim and Christian neighbors. Each of them worshipped with their families – Muslims at the mosque, Catholics at the cathedral, Jews at the synagogue – Eliahu Hanavi – Elijah the Prophet – a beautiful, intricately carved Italian-built structure at the heart of the city on Nebi Daniel Street. And each different group would wait outside for their friends from the other religions to complete their mass or service and then they would gather together at someone’s home to sing and dance until late at night.

Kids rode their bikes in the streets. Everyone knew everyone, and they all respected one another. They were integrated, but not assimilated. Each group kept their unique identity, even though they were friends. Intermarriage among the different religions was rare.

The Europeans didn’t feel like foreigners. Egypt was their country. You could hear a mixture of languages in the streets. At the cinema, movies were played in their original language – English or Arabic usually, with French subtitles, so everyone could speak at least a little of several languages.

Back at the beach cabine, Abdul served Sami some macaroni au four, a baked macaroni and cheese dish he had prepared at home, the perfect comfort after his tumble in the sea. There was never a shortage of food in Sami’s family. They enjoyed frequent large family dinners together and even when they just popped by to visit, his aunts, who all lived close by, would bring out platters of nuts and dried fruit, coffee cake, phyllo stuffed with spinach and cheese, feta cheese, olives and other Mediterranean foods. And his mother did the same when guests showed up in their home. Not being hungry was not an acceptable answer. It was considered impolite to refuse to eat. Il faut manger quelque chose.

It was a beautiful life in Alexandria, a golden age for younger and older people alike, the perfect playground for a young adventurous boy.

Sami was blissfully unaware that Alexandria had been changing for years now, that the peaceful coexistence the Jews and Europeans had enjoyed with the Arabs for so many years was coming to an end.

Politically, the Jews of Egypt had always leaned toward the left – with Zionism, socialism and even communism attractive ideals after the oppression of World War II.

Egypt was part of an Arab military coalition that attacked the newborn Jewish state of Israel in 1948, and an anti-Zionist movement began to form. Jews who were believed to be connected with Zionist groups were arrested, thrown in jail or thrown out of the country. The political climate was changing quickly and some families decided to flee, knowing they were on the blacklist. Papi never talked about politics, but I get the impression his views were more moderate. Eventually, though, that didn’t matter.

There was political corruption in the Egyptian monarchy and a new Republic of Egypt was established in 1953. A revolution against all foreigners – particularly British and French – began to sweep the nation. Fires burned through the city as Egyptians burned down Jewish owned stores, and the beautiful cinemas and cafes symbolic of the British occupation.

The new President, Nasser wanted to nationalize Egypt, claiming ownership of all major assets – factories, fields, buildings, even privately owned companies. He was a charismatic leader who delivered long speeches on the radio. When he decided to nationalize the Suez Canal, which used to be a private company, owned primarily by the French and British, it started the 1956 War.

France and England attacked Egypt, and Israel alongside them, so Egypt began to expel its French and English residents, as well as all Jews, regardless of nationality. First they placed restrictions on importing and exporting, travel, and work permits. They tapped telephone lines, screened personal correspondence. Soon people couldn’t even access their own bank accounts.

Businesses closed, and families left Egypt to head to Brittain, Italy, Spain, France or Israel.

There were rumblings among Sami’s family of leaving. Il faut partir, they’d whisper.

And one night, it was their turn to be evicted from the home they owned, torn from their country, from the only life they had ever known. But even when authorities showed up at their home, garnishing artwork, collectibles, antique furniture, china, cash and jewelry, Jeanette shielded her little boy from the harsh reality of what was happening. When they were told they could each take only one valise, Nana piled layers of clothing onto herself and her son, despite the warm night air, placing valuables in the pockets. Papi hollowed out a large dictionary to hide whatever jewels and money wasn’t confiscated, and entrusted it to Sami to hold onto. For Sami, it was all a fun game, an exciting journey. He wasn’t completely oblivious to the violence and fear, but he never truly worried for their safety, and he had no idea of the horrors and violation that even some of his close family members endured.

They boarded a big ship called The Yugoslavia, and even though it was packed with too many people, Sami didn’t understand that the journey was anything but a glorious adventure. When they arrived in Sardinia, the people threw bread and olives up to the refugees packed onto the ship like sardines.

“Why are they throwing us food?” Sami asked his grandfather. “We play at the beach and have a membership at the country club. We are not peasants.”

They eventually landed in France, staying at a refugee camp in the south for a few months, then moving to Paris where Papi was able to secure a new position with his old company, Banque Belge. My family was among the lucky ones. Despite the traumatic expulsion from Egypt, not speaking the language, and not knowing anything about the local customs and culture, they landed on their feet pretty quickly and began to rebuild from scratch a semblance of the comfortable lifestyle they had enjoyed in Egypt, though they’d never be able to recreate quite the same level of cosmopolitan elegance.

People committed suicide, before and after their departure. Some didn’t want to leave Egypt. They wanted to be buried in their homeland. Others made it to the new country, but living in a refugee camp, they were forced to take entry-level jobs when before they had been heads of companies. Their beautiful life had gone down the toilet like yesterday’s caca.

After about a year in Paris, Papi moved his family to the US, first to New York City and then eventually to the suburbs of Long Island, purchasing a brand new tri-level on a quiet street in Bellmore. Three of his sisters stayed in France and raised their families there. The other three settled in New York, close enough to continue the tradition of large family gatherings. They enjoyed the vast and broad Jones Beach, though it was a far cry from the Alexandrian coast.

My dad had an array of cousins spread out over two continents. The family would always remain close, with a fierce love and a strong bond that I didn’t know was uncommon in families.

By the time they got to Bellmore, my dad started introducing himself as Sam, and he would practice speaking English for hours in front of a mirror, trying desperately to erase all traces of his Egyptian French accent so he could be just like the other kids.

“That’s an interesting accent,” people would say to his parents. “Where are you from?”

They would respond vaguely that they were French, rarely mentioning Egypt, because it was too complicated to explain that they were from Egypt, but not Egyptian.

“Malka, such an interesting name. Is that Italian?” others would ask.

They usually avoided explaining that actually, Malka is the Hebrew word for Queen. It wasn’t that they were embarrassed to be Jewish exactly. They were proud to be Jews, but it had always been a quiet and personal faith, even before it had become a crime just to be Jewish in their home country.

Papi was all about picking yourself up and starting over, focusing on the good. Focusing on his family and their health and safety. He knew that you can’t go back. You must move forward.

In a 2016 documentary called Starting Over Again, my dad’s cousin Yves said, “The Jews of Egypt are one of the best examples of resilience because they survived and adapted all over. We saw our parents fight back after they were humiliated. They stood up and gave us a message of tolerance toward others.”

They loved Egypt, but they were forced to leave it and start over again. They left Egypt, but Egypt never left them, someone else said.

Another Egyptian Jew in the documentary, Alec Nacamuli said, “We have been equipped with tools of understanding and tolerance that at the end of the day could be a bridge to get to the other side.”

This resilience and strength tempered with tolerance and understanding was ingrained in me from childhood, but I never fully realized the drama and the trauma in my family’s expulsion from Egypt, and until I saw that documentary, I didn’t understand how common their story was, how many of us there were. When I watched it, I felt a nostalgia for a place I never even knew.

Even though most Americans have never heard of this “Second Exodus” of the Jews from Egypt, I had heard the story so many times as a kid. I’d always ask questions, wanting to know more, but Nana and Papi gave me only a vague picture, glossing over the horror like it was a cute little parable. They really did just move on, start over and never look back. Papi never even wanted to visit Egypt. America was his homeland now.

My father succeeded in erasing his French accent and becoming a part of the American melting pot, a carefree American guy, popular with the ladies (he did sometimes use the French strategically). And he remained particular about his toys, or really anything that was his. In college he’d hide a quart of gourmet ice cream inside a huge tub that had once held some hideous flavor he knew his roommates would overlook in the freezer. On the surface, he hadn’t changed a bit from the adventurous enfant gaté he had been in Alexandria.

But if you looked closely, you’d notice he had no emotional attachment to the things he seemed to prize more than people – whether electronics or cars, houses or boats, he always held them lightly, happy to sell if he got the right price, excited to move on to the next shiny object. He took meticulous care of his things, but said goodbye to them without a second thought. Because he was always eager to try something new and never one to set down roots, we moved every few years as a kid, which made it hard for me to form attachments and deep friendships, too.

My dad has always avoided emotional life events, anything that might make him feel sad or scared. Though he was married to my mom for more than 20 years, and even still remains close to her after more than 20 years of divorce, he always seemed emotionally unavailable to me. I knew he loved me, but I rarely caught a glimpse of his deepest thoughts and beliefs about life and love.

I wonder, after all these years, if any of his quirky personality is a result of the trauma of being ripped away from his home at nine years old. And as I think of that, I want to give him a big hug and let him know that it’s OK to cry. Sometimes life just really sucks. But it does get better. And I wonder if my own desire to delve right into the messy emotional side of life, my constant search for community and connection, my desire to build a bridge between any two opposing parties, and to always move quickly toward joy and silver linings, never resting too long in sadness, was at least partially formed from this thread of my ancestry running through my own life.

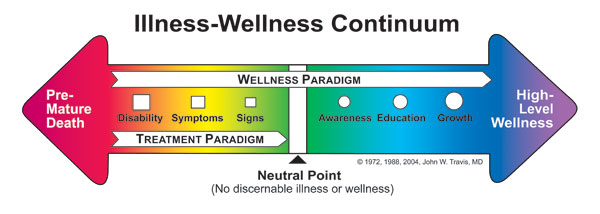

Figure 1.1 (Brookside, 2015)

Figure 1.1 (Brookside, 2015)