Pink and Blue – a Poem

I love the color blue. But not on a baby’s skin. For skin we want bright pink.

Blue ok on feet and hands. Immature circulation, normal. Not face, not lips, not chest.

My stethoscope is baby blue. No baby’s chest should match it.

Cut the cord quick. Get her to the warmer. Start NRP.

I stand there at attention, ready to take the order.

Shouldn’t be that color. Not pinking up.

Did she cry? Did she make a sound? I can’t remember now.

So many births. They start to blend together.

But can’t forget that blue blue chest, my stethoscope against it.

“Can you hear anything at all?”

I strain to hear the thready beats, too slow. Breaths too soft to hear.

I count. Only 60 beats in 60. Too slow. Too slow.

In utero, it was 175. Too fast. Distress.

Still too blue. Chest isn’t rising. Red button. Call NICU.

Oxygen mask on nose and mouth. Heartbeat going up. 130, that’s better.

They come so fast, thank God. A team including doctor.

Suction! What happened?

Maternal fever. Fetal tachycardia. Baby in distress. Meconium aspiration.

Tylenol brought down fever. IV antibiotics in. Black hair, blue body. Green placenta.

Send it to path. Get cord gases.

Suction! Mec is hard to breathe. Got more than we thought. Intubate!

We’ll take her for a while. Help her clear her lungs.

Mom moves to postpartum, no baby in her arms. Goes to visit NICU. She’s holding on but barely.

I wake up breathless. Seeing blue. I send my love and light.

I love the color blue, but not on a baby’s skin. Pink. Pink. Pink on a baby’s chest and face.

Not blue. Not green. Not blue.

*Details have been omitted or changed to protect patient identity and privacy. Sorry for being so dark. Being a Labor and Delivery nurse is the most joyful job in the hospital, except when it’s not. I usually leave the poetry to my daughter, but have found it surprisingly therapeutic to write the images that keep me awake without attempting to form them into cohesive paragraphs or assign deep meaning.

Moving Along the Illness-Wellness Continuum over a Lifetime

This is not my typical blog post, but a paper I had to write for my GCU nursing class. Since much of my creative juices are currently being directed toward nursing school, I figured I might as well publish some of my work here on my blog!

Moving Along the Illness-Wellness Continuum over a Lifetime

Danielle Tantone

Department of Nursing, Grand Canyon University

NRS-434VN: Health Assessment

Geraldine Bazzell, RN, MSN

1/31/21

Just over a year ago, I was enjoying a peaceful September afternoon at the park with my youngest daughter in the midst of a crazy stressful life: three kids, nursing school, working nights at the hospital as a nursing assistant.

The blazing summer heat had broken, and it was finally cool enough to enjoy the outdoors in Arizona. My cell phone rang, and my doctor gave me the life-changing news that I had breast cancer. But I was neither shocked nor alarmed. I was high-risk and had gone in for a biopsy two days earlier after my mammogram showed some microcalcifications.

I had done my research, so when she told me that the biopsy had revealed high grade, Stage 0 ductal carcinoma in situ, the earliest form of breast cancer, my mind went right toward making a plan and focusing on all the silver linings, of which there were many.

I had just turned 45 and I was at a healthy weight, eating a healthy diet and exercising regularly. I decided almost immediately that the best treatment option for me was a bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction. Yes, I could have chosen “just” a lumpectomy, but by choosing the double mastectomy I avoided chemotherapy, radiation and even hormone therapy, all of which, to me, were far more invasive than simply removing the breasts which had served me well but were no longer strictly necessary.

I believe that the healthy mental attitude I chose to adopt during this health ordeal was just as important as my physical health, and despite my serious disease diagnosis, I stayed in a state of overall wellness throughout the entire ordeal.

Wellness has many components: physical, mental and emotional. Though it can be pictured as a continuum, along which we all move back and forth throughout our lifetimes, it is actually a multi-dimensional concept that is hard to completely understand on a one-dimensional model. One can be sick in terms of disease, but rate high in terms of overall wellness, or one can be free of disease but not enjoying a state of overall wellness at all (Wellness, 2018).

The goal is to be not just free of disease, but in a state of optimal wellness as much as possible over the course of a lifetime. As nurses, it is important to be aware of our patients’ – and our own overall state of wellness and not simply look at whether or not we are experiencing symptoms of disease.

The origins of the Illness-Wellness Continuum

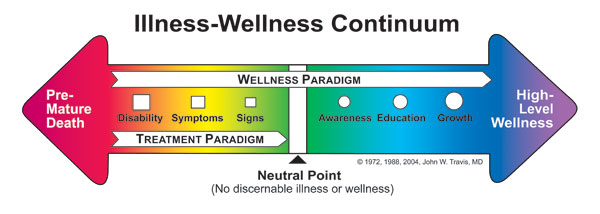

The health-illness continuum, originally conceived and published by John Travis, MD, MPH in the 1970s, provided a nice picture to show how optimal wellness was achieved by moving past simple absence of disease to higher levels of wellness. The idea was a combination of the Lewis Robbins’ health risk continuum created by Lewis Robbins and Abraham Maslow’s concept of self-actualization.

However, the model makes it hard to understand the fact that it is possible to be physically ill but oriented toward wellness, or physically healthy but suffering from an illness mentality, and the continuum is rarely a perfect line. Even if someone is sick, in a disease state, they can still be doing very well in terms of overall wellness (Wellness, 2018).

More About the Illness-Wellness Continuum and Travis’ Work

Moving from the center to the left shows a progressively worsening state of health, while moving to the right of center indicates increasing levels of health and wellbeing. While medical treatment such as drugs, herbs, surgery, psychotherapy, etc. alleviates symptoms and brings a patient to the neutral point, the wellness paradigm can be utilized at any point on the continuum, and directs a patient beyond neutral. This idea of true wellness does not replace treatment, but works in harmony with it (Wellness, 2018).

A state of emotional stress can lead to physical and mental disease, even cancer, and true wellness is not a static state. In fact, it’s not as important exactly where a patient falls on the spectrum so much as in which direction he is headed. Even dying can be done from a place of wellness (Wellness, 2018).

The Importance of Understanding the Continuum in Patient Care

The health-illness continuum also interacts with the continuum of patient care. In a healthcare system that is often criticized for focusing on acute conditions rather than wellness and prevention, thinking of wellness in terms of a spectrum has advantages for everyone involved. A truly patient-oriented system of care “spans an entire lifetime, is composed of both services and integrating mechanisms, and guides and tracks patients over time through a comprehensive array of health, mental health, and social services across all levels of intensity of care” (American Sentinel University, 2020).

Such a system would provide high-quality and cost-effective care for patients using community-based services such as home health nurses, telemedicine, disease management programs, informatics, and case management. Nurses are essential within this continuum of care. They support treatment, help educate and guide their patients toward better health outcomes (American Sentinel, 2020).

Nurses must consider not only the continuum of care, but also pay attention to where each patient is within his own health-illness spectrum, always remembering to look at the patient holistically. A nurse’s role goes far beyond simply treating disease. She can have a tremendous value in promoting overall wellness on every level.

Nurses’ Personal Place Along the Health-Illness Continuum

On another note, nurses must pay close attention to where they, themselves are along the continuum as well, since they can’t very well take care of others if they aren’t taking care of themselves first. Studies have shown that nurses experience more musculoskeletal disorders, depression, tuberculosis, infections and occupational allergies than the general public. Nurses’ shift work was shown to lead to sleep deficiency, lack of exercise, cardiological and metabolic problems, and even cancer (Letvak, 2014).

And while the nurses’ health is important, it is not just about them. Studies also show that nurses who work with physical and mental illness experience more medication errors and patient falls, and offer an overall lower quality of patient care provided (Letvak, 2014).

According to the ANA, “A healthy nurse lives life to the fullest capacity, across the wellness/illness continuum, as they become stronger role models, advocates, and educators, personally, for their families, their communities and work environments, and ultimately for their patients” (Letvak, 2014).

The ANA offers many levels of support for nurses on their own journey along the health-illness continuum.

Health is in a Constant State of Change

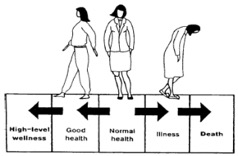

A person’s health is always in a state of continual change on every level, moving from health to illness and back again. His condition is rarely constant. The health-illness continuum (see figure 1-1) illustrates this process of change. Each individual experiences various states of health and illness throughout his life. But it is actually the individual’s response to the change, rather than the change itself, that affects his health most profoundly (Brookside, 2015).

Figure 1.1 (Brookside, 2015)

Figure 1.1 (Brookside, 2015)

Adaptation to a chronic disease can be considered a state of wellness. If one person is in great physical condition, but suffering from depression or substance abuse and unable to go to work, while another is living with a chronic disease like diabetes but functioning fully within his life, which one is at a higher level on the health-illness continuum (Brookside, 2015)?

Where I See Myself on the Continuum

I have always thought of myself as an overall healthy person. I know my body well and I take care of it. However, I have not ruled out the possibility that the physical and emotional stress I was under in 2019 actually led to my breast cancer. I was dealing with a lot and I was working the night shift, which has been proven to throw off the body’s circadian rhythm. Some studies even show a link between shift work and cancer (Yuan, 2018).

So, in that moment, I was heading toward illness. However, the fact that I was being regularly screened and took prompt action to treat the cancer, and the fact that I chose to see all the blessings in my diagnosis turned me around toward the wellness end. Facing illness with eyes wide open, trusting God and having a strong support system are huge in terms of wellness.

Conclusion

As an aspiring nurse, I find it encouraging that we are learning about the health-illness continuum. I feel very strongly that good healthcare is so much more than simply eliminating disease. As nurses, we can have an impact of the overall wellness of our patients and the entire community. The patient care experience, like the human experience itself, is about so much more than just staving off disease. Nurses can have an impact on a person’s entire life through their compassionate caring, empathy, education and love. A good nurse can encourage, inspire and comfort her patients, promoting dignity in the most embarrassing of situations and helping a patient turn back in the direction of wellness no matter how sick they are.

It is important that nurses do not forget to treat themselves as their most important patient, taking care to get enough sleep, exercise, healthy food and mental, emotional and spiritual stimulation. It is a stressful and important job we do. We hold our patients’ lives in our hands. We must never take our own health for granted or think that it is unimportant.

I am grateful that I got cancer. I am glad I got to experience what it is like to be a patient. I am grateful that they caught it early and that through my journey, I have been able to encourage so many others – to get regular screenings, to not be afraid of bad news, but to welcome it because getting the news lets them do something to fix it, and to face their challenges with grace and faith.

References

American Sentinel University. (2020). What is the Healthcare Continuum of Care and What Are the Different Nursing Roles Within it? The Sentinel Watch. Retrieved from https://www.americansentinel.edu/blog/2020/02/15/nursings-role-in-the-continuum-of-care/

Brookside. (2015). The Health-Illness Continuum. Nursing Fundamentals 1. Distance Learning for Medical and Nursing Professionals. Retrieved from https://brooksidepress.org/nursing_fundamentals_1/?page_id=115

Letvak, S. (2014). Overview and Summary: Healthy Nurses: Perspectives on Caring for Ourselves. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing Vol. 19, No. 3, Overview and Summary. Retrieved from https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-19-2014/No3-Sept-2014/OS-Healthy-Nurses.html

Wellness Associates. (2018). Key Concept #1: The Illness-Wellness Continuum. Retrieved from http://www.thewellspring.com/wellspring/introduction-to-wellness/357/key-concept-1-the-illnesswellness-continuum.cfm.html

Yuan, X., Zhu, C., Wang, M., Mo, F., Du, W., Ma, X. (2018). Night Shift Work Increases the Risks of Multiple Primary Cancers in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 61 Articles. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. Retrieved from https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/27/1/25

Danielle,

Thank you for sharing about your diagnosis and a bit about your journey with breast cancer; this is a perfect example of how emotional health impacts our placement on the continuum. Good discussion of each section of the assignment. This is one of the best submissions I have had for this assignment. See comments throughout for learning opportunities.

Geri

Final Breaths and Other Small Things

His breaths had slowed to such an interval that by the time they stopped, I stood there for several minutes with my hand on his chest to be sure that it was no longer rising and falling.

I wasn’t entirely sure he really was gone until the nurse came in with her stethoscope and confirmed it. And even then, as I stood by his bedside a few minutes later and watched him, I kept thinking I could still see his chest rise ever so slightly.

Though I had previously sat with both family members and patients close to death, and had even had the strangely beautiful honor of bathing and caring for tiny babies who had died in utero when I worked in Labor and Delivery, this was the first time I had actually seen a person take his final breath, watched him cross over from life to death.

Being the one who stood by his bed in the moment he passed was a blessing and an honor to me.

His death was expected. He was on hospice and had been making the slow decline for months already.

I had only been caring for him for six weeks, laughing as he turned his nose at the pureed meals we tried to feed him and demanding instead a steak, a cheeseburger, a coke.

I couldn’t blame him. Those scoops of pureed food plopped on the plate were anything but appetizing. It seemed a cruel reality that in his final days he couldn’t enjoy his favorite foods, but he had no teeth and couldn’t chew or swallow well. He would aspirate if we tried to give him the foods he so desired.

Thankfully we were able to get him some soda. He would close his eyes and a smile would spread over his face as he sucked up a sip of ice-cold coke through the plastic straw we held in his mouth for him. I wondered what memories the spicy bubbly drink brought back for him.

Sometimes he would share bits and pieces of his life, and I could see glimpses of the man he once was, but it was like trying to imagine technicolor on a black and white drawing, or putting dialogue into a silent movie.

Laying there in that hospice-provided bed in his room in the long-term behavioral care facility I had been working in, I knew he was just a shell of the person he once was.

He could be taciturn and cranky these last few months as he declined. But I loved him anyway.

Even though he rarely wore more than a hospital gown anymore, he often asked me to check his armoire and count his clothes. I guess he wanted to make sure they were all still there. He wanted to wear his glasses and his watch, even though there was nothing much to see and he had nowhere to be.

Sometimes he called me Mama, and other times he told me I was a pretty girl and asked if I was married, praising me for my gentle care. Still other days he angrily swatted at me as I tried to change him or clean him up. He said he wanted to go home and demanded I call his parents. (I didn’t know his exact age, but I was fairly certain his parents were no longer alive.)

In the last few days leading up to his death, he was no longer drinking his Coke or Ensure. We would only moisten his mouth with those little pink swabs dipped in water. The nurses had alerted the hospice that he was in the active phase of dying. It would be a matter of days at most.

When I came in early that morning and checked in on him, I could hear the crackle in his breath, like there was liquid in his lungs – “the death rattle,” the nurse confirmed. He was close.

I asked her if he had any family who would come today. In the days of Coronavirus, imminent death is the only time patients can have visitors, even when they weren’t dying of Covid-19. But no one would come for him, she said.

“I guess we are his family then,” I said, my voice breaking just a little and tears forming in my eyes.

“Yes, I guess we are,” she said, smiling.

At that moment I decided it was my job to make sure he didn’t feel alone or afraid. And so, throughout the day, I peeked in on him frequently even though he was not one of my assigned patients.

I sang to him as I helped the other CNAs give him a final bed bath and change his linens and gown late in the morning. He was still breathing peacefully when they asked me to do a double shift, and I was happy to stay and be there with him, even though it would mean a 16-hour day and missing out on Friday night family time.

A few minutes into the afternoon shift, the nurse told me it would be anytime now, maybe only minutes, so I paused my rounds to stand by his bed and sing some more.

Aside from the hum of his roommate’s oxygen machine, his TV news reporting the latest Covid-19 stats and campaign briefings, and his light snoring on the other side of the curtain that separated their beds, along with various voices and noises from the hall as life went on out there, it was quiet and peaceful in that room. It was hard to even pinpoint the moment when he crossed over from life to death.

I saw him take a slow breath, then many moments passed before he took another. He was staring blankly toward the window, no longer squeezing my hand in recognition when I held it. He was slipping away. I said a quiet, neutral prayer and sang a few more songs.

There was no dramatic final breath. I just watched and waited for another rise and fall of his chest that never came.

After his death was confirmed, the nurse made the necessary calls and arrangements and we gently closed his eyelids and wedged towels under his chin to keep his mouth from gaping open. A few staff members came by to pay their respects.

I had other work to do, but I stopped into his room frequently over the next few hours until a van from the mortuary came to pick up his body. I was the one to answer the call from the front desk that someone was there to pick him up, then run over to the other side of the building where he had pulled up and direct him to the circular drive outside our unit instead.

Such simple, small tasks, but they seemed so important to me.

And then he was gone and his bed was empty. And I went about my day, taking care of all the other residents.

Serving then cleaning up dinner. Finishing the puzzle we had started in the day room earlier that week. Cleaning up messes. Diffusing anxious behaviors. Helping everyone to bed. Charting. Sitting for just a few minutes to visit with a resident and at the same time rest my tired feet. The hours passed quickly.

The next day after sleeping in following my double shift and emotionally draining experience the day before, I attended a virtual memorial service for a woman from my church who had also just passed away. She had been a missionary in Africa for many years – teaching a course called Mending the Soul to people who had endured trauma and abuse, before getting sick with metastatic breast cancer last year. I had only met her a handful of times, but had found her life and work so inspiring.

I had the privilege of visiting her at home a few weeks earlier as she battled her illness. I prepared a few simple meals for her while she rested in bed before my evening shift at the nursing home. I’m so glad I followed my instincts and said yes to the request to serve her, even though I was busy. I wanted to visit with her more that day, share our stories with one another, but she was very tired and I wanted to spend some time with my family before work, so we said we would do it another day. I was sad to hear that she died before I got the chance to visit again.

The memorial was a beautiful celebration of her life of service and love. And as I listened and watched from my comfy couch at home, contemplating her life, my patient’s life and my own life, I thought about how I’d like to be remembered when my time comes.

As I think is common in times like this, I felt both inspired and chagrined by the impact she had made on the people she touched. I felt like I’d only barely begun to make a dent on the great things I’d like to accomplish with my own life, and I wasn’t sure if I had made much of a difference so far.

But toward the end of the service, the speaker shared an African proverb which eased my anxious and constant pursuit to do big things and reminded me that what I was already doing every day was meaningful and important.

“Many small people, who in many small places, do many small things can alter the face of the world.”

I think this is a great reminder to us all to just be present where we are right now.

To do what we can even if it feels small.

To feel all the emotions and not try to numb them.

To love even the unlovable and to do the hard things.

To find and create acceptance, joy, delight and peace in the little things.

To take a breath when we are tired or overwhelmed.

To notice the beauty around us and then take another breath.

It was a reminder that the smallest things are sometimes the greatest things.

The Real Reason I Bust my Butt Wiping Butts for a Living

It’s hard to believe it was only just over a year ago that I went from cushy and clean office jobs to the messy manual labor of patient care in order to get some experience as I become a nurse.

There have been many moments when I wondered what the hell I was thinking – like the first time I emptied a colostomy bag (literally a small bag of poop that comes directly out of a patient’s abdomen).

Or the time I was helping a patient use the bedside commode and the bucket base that serves as the toilet fell to the ground, spilling about a gallon of urine all over the floor.

Or the many times I forced myself to keep smiling instead of gritting my teeth as a patient yelled at me because I wasn’t wiping their butt correctly.

In these moments I’ve wondered why in the world I would ever have made such a change. I’ve imagined myself floating up above the situation, looking down and just laughing at myself.

Ha! You wanted to be a nurse?! Did you ever think you would literally be cleaning up shit for a living? You’re a professional butt wiper! And even though people like to talk about how much money nurses make, your first-year base salary in employee benefits consulting was more than your annual salary will be – in three years – once you become a nurse! And people get paid more than you’re making now to work at Salad and Go or Chick Fil A! What were you thinking??

But that man with the colostomy bag? The one they told me was a grumpy, nasty jerk? He was so gracious with me, calmly instructing me on how to empty it, and ensuring we didn’t get poop all over. He had been doing this for years, after all. Can you imagine that? Having to empty out your own poop from a bag attached to your belly? You might be a little grumpy too.

I smiled and joked with him even as I helped with this unfathomable task. I had already learned how to breathe out of my mouth so I didn’t smell all the smells.

And once we were done and had cleaned up, I lifted the clear graduated container that held the excrement up to my eye level, noting its volume in order to chart it for the nurse. The patient muttered something about the color being darker than usual, almost black. Hmm, I said, not thinking much of it. I tucked him in, emptied the container into the toilet, rinsed it out and set it in the bathroom for next time. I turned off the light, left the room and went to the computer at my workstation to chart the output, remembering to note the blackish color.

A little later as the nurse reviewed his chart, she asked me to comment more precisely on the color of his poop, and as I was trying to describe the exact color, I remembered from nursing school that feces often looked black when it contained blood. In that moment, I also recalled that when I checked his vitals a few minutes earlier, his blood pressure had been pretty low and his heart rate had been pretty high.

It turns out this man was bleeding internally! And it was his poop that was the first indicator. And if I hadn’t done my job so thoroughly, if I hadn’t taken the time to note the color of his poop, he might have died. No wonder he was grumpy! That was the moment I realized that it was worth it. That this was important work. That my job mattered.

The lady with the spilled urine was also a difficult patient. She was suffering from an unexplained partial paralysis that seemed to be psychosomatic and pretty inconsistent (i.e most of the nurses thought she was faking it), but I calmly transferred her from bed to commode each time she had to go (which was many in that 12-hour shift). She watched as I calmly sopped up the pee with towels and lovingly cleaned her up and got her back in bed with a smile.

“You are the only one who has been nice to me,” she said. “You are so patient and kind, even in this embarrassing and messy situation. You are going to be a wonderful nurse. Thank you.”

And the people who yell at the way I wipe their butt? Well, I know that they are just in pain – physical, mental, emotional or all of the above. Sometimes they apologize later and sometimes they don’t.

And I decide, again and again, that my job as a nursing assistant, though it looks different in practice, is in theory the same as any other job I’ve ever been good at.

Whether I’m writing stories, singing songs, helping people buy and sell homes or insurance, raising kids or cleaning up messes, my job is to help, serve, comfort, encourage and inspire the people with whom I come into contact. I don’t always do it well. But my goal is to leave people feeling better than they did before our encounter.

I have taken care of hospital patients recovering from surgery or suffering from heart failure or stroke, hospice patients on palliative and comfort care only, moms and babies in Labor & Delivery, patients suffering from Covid-19 and schizophrenic patients with aggressive behaviors.

I have worked for two of the major hospital systems in my county, and even took a short-term travel CNA assignment at a behavioral health facility this summer as I geared up for “Block 1” of nursing school to start in late August. It paid three times more than my regular fulltime gig at the hospital and opened my eyes to so much – I learned about travel nursing, nursing home administration, behavioral health and taking care of psych patients – and I continued my lifelong study of people, love and life.

A friend of mine said recently that she chooses to think of her job as a nursing assistant as a sort of paid internship. And I think that’s the best reason to do this kind of work. There are definitely better ways to make a living – even during a pandemic. But I have learned and experienced so many lessons about nursing in such a short time. Lessons that you just can’t get from a classroom. Experiences of a lifetime. I’m also showing my kids that we can do hard things, and that there is value in good old- fashioned hard work, even though there are new ways to serve the world and make a living.

Nursing will never be the only thing I do. I will always also be a singer, a writer, a coach, a consultant, or whatever else I decide to become. I still believe the words my mom instilled in me as a child – that I can do anything I set my mind on.

But whatever I do, wherever I go, I will always try to make people feel just a little better than they did before. I won’t always succeed. Sometimes I’ll rub people the wrong way. I won’t be for everyone, and that’s OK. I will keep on smiling, even under a mask that makes my chin break out like a teenager’s.

Dealing with the Death in “Coronavirus Time”

My precious four-year-old refers to this time as Coronavirus Time. To her it’s a happy time with lots of snuggles and baking.

Even when my Uncle died of Covid-19 last month, I don’t think the dots connected for her. And I’m OK with that. Frankly, I don’t think the dots connect for a lot of us. Even after watching my uncle struggle to breathe as he suffered from the virus, I find it hard to wrap my head around just how much this little virus has changed our society in such a very short time. And I struggle with what’s right and good and helpful, and what’s just not — just like you do.

But this isn’t about that. This is just a personal story of my experience dealing with the death of a loved one in “Coronavirus Time.”

I feel lucky to have been able to go in with my mother to see my Uncle Howie the day before he passed away from Covid-19 — in full PPE: gowns, N95 masks, face shields and gloves. I got to hold his hand (with gloves on), help his caretakers move him into an adjustable hospital bed provided by hospice, sing to him — from Hebrew prayers for healing to 60s hits to make him smile.

By the time we got there, he was unable to speak, though I could tell he was trying to. Whether he wanted to whisper a somber goodbye, an expression of pain or one of his trademark corny jokes, I’ll never know. But I could tell he was still in there, could hear us, and knew that we were there for him.

Not everyone is so lucky to see familiar faces as they breathe their last breaths these days, as hospitals and nursing homes have closed their doors to visitors in order to prevent the spread of Covid-19.Though some hospitals will allow loved ones to visit in “end of life” situations, as we were able to do, this is not always the case.

It was scary to arm myself in personal protective equipment and go into a building where the virus was known to have infected several patients, to come into direct contact with my uncle, who hadn’t been tested yet, but presented with all the symptoms.

Though I work as a nursing assistant in a hospital, I hadn’t yet experienced the donning of full PPE for protection from Covid as I was just coming back after a six-week leave of absence following breast cancer surgery. In my new job in Labor and Delivery, we now have to wear an N95 mask and face shield in most deliveries, as the pushing phase of labor and all that heavy breathing emits droplets into the air. I’ll admit, it’s not easy to breathe through all that, and I worry about the long-term respiratory effects of all of us nursing staff breathing through even the regular surgical masks for 12 hours straight.

But listening to my Uncle Howie struggle to breathe and not being able to do anything was excruciating. He was on oxygen, but his breath still came in quick, irregular and obviously painful rasps. We cleaned his face and mouth, removed his dentures, helped him to sip a little water from the little sponges that I asked the nursing staff to bring in for him.

In that moment, my nursing instincts kicked in and I didn’t really think about the gravity of it all. I just wanted to do whatever I could to make him more comfortable. I feel so very lucky to have been granted that opportunity, and to me it was well worth the risk.

While we were there, the hospice nurse came to check in on him. He told us his death was inevitable now and it wouldn’t be long. He increased his hourly doses of morphine to help his breathing and dull the pain. Uncle Howie passed away before dawn the next morning.

We found out more than a week after his death that he did indeed die of Covid-19. They tested him post-mortem. To me there was never a question. It was just like the images and descriptions I’ve seen of the way the virus ravages the lungs. Still, hearing the actual diagnosis affected me. And reliving the experience of being there, up close and personal, a wave of sadness and anger and grief I had pushed right through before came over me.

I had posted about the visit on Social Media. Here’s what I wrote…

A picture is worth 1000 words. They let my mom and I in to my Uncle Howie’s assisted living facility today in full PPE. (My wonderful sister was there, too, but she stayed outside per my mom’s request. She didn’t really want me to go in either, and I didn’t want her to, but we are both stubborn!)

The facility has been closed to all visitors for more than a month but they make exceptions when someone is near the end of their life.

We were only there for a few hours, but it was an emotional adrenaline rush followed by a big crash. He’s still hanging in there now.

Though he has not been tested, there have been confirmed cases of Covid-19 in his facility. He’s presumed positive based on his symptoms. They won’t take him to the hospital because he’s on hospice now. They are just trying to keep him comfortable.

It was horrible to see him struggling to breathe, but I’m so grateful I was able to be there with my mom. No one should have to face death alone. That’s one of the worst parts about this virus and situation. Hug your loved ones and stay safe.

My sweet Uncle Howie has lived a long and wonderful life, 50 plus years more than he was expected to live. He survived a bad car accident at 25 that put him in a coma for months and left him permanently brain-damaged. But he always had a smile on his face and a corny joke for anyone he came in contact with. He will be missed.

We spoke with the hospice nurse just now and he said he’s resting comfortably and will probably make it through the night. Big hugs

And the next day I posted again after he passed…

Our uncle Howie, Mom’s big brother, died early this morning at his assisted living facility in Phoenix. He would have been 79 this May.

As I said in my post yesterday, he was a loving, joyful man who lived more than 50 years longer than he was expected to after surviving a bad car accident at age 25 that put him in a coma for three months and left him permanently brain damaged. He always wanted to make people smile and told the corniest jokes.

I have so many fond memories of Howie. Before Grandma died, he lived with her in New York and I loved hanging out in his little room at Grandma’s house. He had so many treasures. He walked with a cane but really didn’t seem brain damaged to me. He was just my wonderful uncle.

After Grandma died in 1984, Mom moved Howie here to live in Arizona. He had his own private apartment in a large group home for many years. We would spend hours there on the weekends, mostly just hanging out while my mom made sure Howie was in good shape physically and emotionally. She was so amazing. His primary caretaker with so much weight on her shoulders for so many years. We all are lucky to have her in our lives, but she and Howie had a very special bond.

And having Howie in our life, spending so much time surrounded by the other people at his residence with various disabilities, we learned to love, respect and talk to people who were different. It gave us a compassion and an understanding that I didn’t realize was unique.

Mom moved Howie into the assisted living facility about 10 years ago. Of course he was loved there, too. He was loved everywhere he went.

My mom may not be a nurse, but she showed me what it is to be one, how to take care of a person selflessly, doing the messy jobs, sacrificing time and energy for another person. She taught us how to be a good sister and a good person.

The hardest part for us is not to be able to be together to mourn and celebrate Howie’s life. Because I’m sure he would say that it was a wonderful life. Rest In Peace, Uncle Howie. You will he remembered!

Mourning in a Pandemic

Everything is more complicated when someone dies now. All those things you need to coordinate and take care of, even the funeral or celebration of life, is affected. And there is a distinct lack of the social contact that is so very comforting to the mourning.

For Uncle Howie, we did a very small drive-by funeral at the cemetery. Only immediate family — my mom in her own car, my sister and her family in their own car, my dad in his, and me and my family in ours. The Rabbi, who’s also a close family friend, stood at the graveside maybe 100 feet away (I’m not good at estimating distances). Her words broadcast into our car via FaceTime so we could hear her as well as see her.

We emerged from the cars only briefly for a certain prayer that required us to stand. But mostly, the Rabbi said, for the first time in her life, all bets were off as far as what was “usually to be done” at a Jewish funeral. After the short somber service, each car went its separate way. We didn’t even gather for a meal together after.

We skipped the Shiva all together. Shiva is normally a sitting in time, a bit like a Catholic wake but different. It lasts a week, and relatives and loved ones come visit the mourners and bring food, reminisce and say prayers. Rabbi offered to do it virtually for us, but my mom didn’t want to do that. Some family members still wanted to send us meals, so we spread out in the grassy common area behind my mom’s condo with blankets and tables, and tried to keep the kids at least six feet away from their cousins.

A few days later, we met on my sister’s driveway and dined on Italian food.

I have seen friends grapple with the death of their own loved ones in recent weeks. Everything is hard. From not being able to visit them sick in the hospital, to recovering their things, to planning funerals and celebrations of life.

Life is just different now. And death is too. But we take a breath and we move on. And perhaps we are just a bit more thankful for each breath we do take.